21 May 2018

Interview

SYOWIA KYAMBI’S NEW MYTHOLOGIES

Syowia Kyambi works in many layers. Her current work ties in with previous performances, which are based on stories, histories and universal mythologies. She is working on the island of Suomenlinna until the end of April 2018, tying in loose ends and coming up with conclusions.

Syowia is not planning on performing anything whilst in Finland. She is currently in an incubatory mode, and the location of Suomenlinna works for that. She is currently at a stage of figuring out her next step, and is taking advantage of the secluded nature of the island. Her performance project of many years, Between Us, involves a full crew of 5-7 people, which is why a performance at this moment of thinking and brewing new ideas would be difficult and distracting.

A performance in three chapters: the Between Us Trilogy

Syowia’s ongoing body of works is called Between Us. It is a trilogy with three characters. It also involves a fourth addition in the form of an installation, some body prints and a book about the whole complete body of works and its coming to be. The first and second part of the trilogy have been presented already (the first chapter was performed through crowdfunding already in 2014), but the third one is still looking for the right time and place.

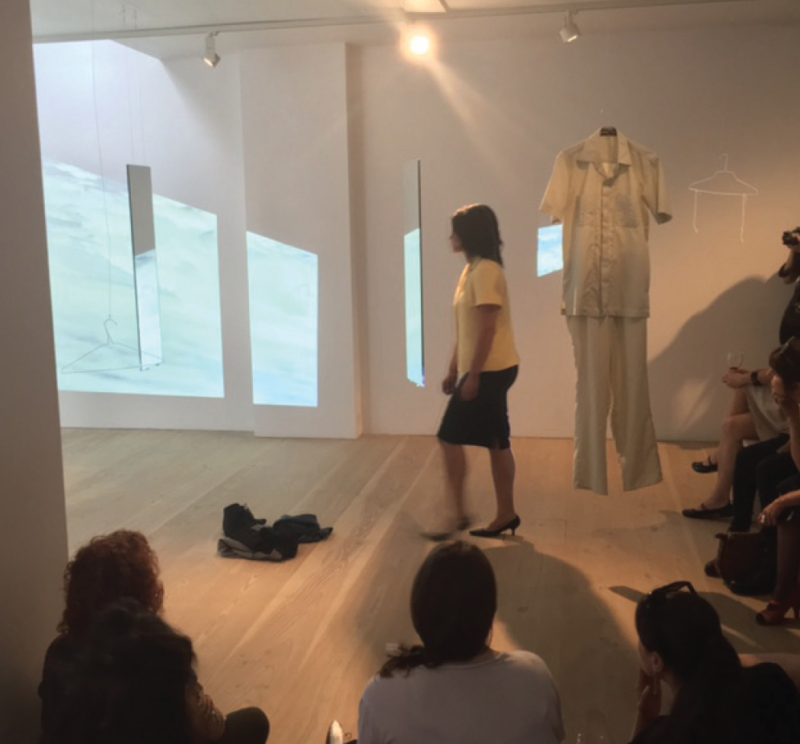

The performance (in three chapters) tells the stories of three characters: a businesswoman, a domestic worker and a man in a Kaunda suit. In the first chapter of the performance the character of the businesswoman is walking against a wall repeatedly. If you’re in the way, she doesn’t register that you’re there. She does that until she unravels. Then she undresses and wears domestic worker’s clothes and becomes the domestic worker. In the second chapter the businesswoman is very robotic, and the domestic worker repeatedly dresses her and undresses her. In the third chapter the businesswoman tears apart a Kaunda suit.

The Kaunda suit is a nationalistic symbol. In the 60s and 70s they were worn on the African continent by statesmen and everyday business men, celebrating post independent area pride. The Kaunda suit is suitable for the climate but still very western, featuring short sleeves but no tie. There is no female version of the Kaunda suit. The Kaunda suit has experienced a power shift in more recent years: these days it is worn by employees, school bus drivers and so on, and is no longer associated with power. When the businesswoman tears apart the Kaunda suit, she tears many layers of nationalist history, and even patriarchy.

The man who is wearing the Kaunda suit just sits and watches; he is just an observer. In the second chapter, he is not even there, apart from his suit. The performance features multiple layers of watching an observing. Double sided mirrors are often present in Syowia’s installations, and people are looking at each other knowingly or unknowingly.

The domestic woman is always cleaning and fixing things, throughout all the chapters. There is, of course, a different power shift existing in the domestic woman’s uniform: she is a grown woman dressed in a young girl’s school uniform. As the uniforms are as central to the performance as the characters themselves, Syowia has exhibited the uniforms as an installation.

Erratic body prints

While working at HIAP, Syowia has been extremely interested in making prints with her body, using materials of various kinds for each of the chapters of the trilogy. The body prints reflect on the movements of one of the characters in the performance, the business woman. For example, as the third and final chapter is about regeneration, it would make sense to use ashes for the prints that refer to the third, regenerative chapter. Syowia has realised that people relate to ashes in a negative way, as it brings to them images of cremation and death, and death is seen as a very negative thing. Syowia, however, sees ashes as regrowth, rebirth and regeneration, the Phoenix-bird being a better-known symbol for this idea.

Another material altogether is needed for the second chapter, which is why Syowia has been experimenting with lots of different materials and pigments to see what fits. The body movements of the business woman in the second chapter are connected to why she is such an erratic person in the first chapter – to what made her that way.

For her body prints, Syowia mixes the material with some glue and water, then uses her own body to make prints on paper. She has been experimenting with various materials. Ashes are nice for their regenerative thematic, but leave little detail of the skin. Black pigment and graphite work well, but do not fit the character at this stage. Syowia has also been thinking about using coffee and tea as materials, as pigment – the colonial reference would work well in the context of the performance. The area where the business woman’s character comes from is a tea plantation area.

Apart from experimenting with materials, Syowia has also been experimenting with and thinking about presentation. Some of the body prints have been made on tracing paper, which becomes wrinkly as it dries. The wrinkled paper would not work so well in an installation, but Syowia thinks it might look interesting presented between glass or within a book that she has also been planning.

Invisible inspiration

Another thing that Syowia has been planning while at HIAP, is the making of an explanatory book, that would make her work and all its layers a little easier to read. The book would ideally be handmade, slightly larger than the average book format, and it will include documentation of performances, prints, some clothing and texts.

Syowia would also like to include in the book some of the stories and histories, which have become an inspiration – for example, the story of a woman Syowia interviewed a while ago for another project. The woman had no identification card and was always identified through her father. Now she is extremely self-sufficient. Her life experiences are also a power shift, just like the power shifts reflected by the costumes in Syowia’s work.

Also, parts of the everyday routines and rituals make it into Syowia’s work. For example, underwear washing in public is considered very taboo in Kenya, and drying underwear in public is something that must never be done. This is why in a performance of the first chapter of the trilogy, there was underwear washing.

This is all invisible research and inspiration, which is why a book would be a good platform to share it with the audience.

Another story that angers Syowia is that of the rape and attempted murder of a young girl a few years ago. The girl was lucky enough to be found and rescued. However, the first ruling the judge gave to the perpetrators was for them to cut grass as punishment. Thankfully, the women’s rights movement jumped in and changed the punishment. However, situations like this are enough to make anyone erratic, as happened to the business woman in Syowia’s performance trilogy. The woman becomes erratic and then robotic, and she gets partial retaliation as the man, the patriotic and nationalistic symbol, is torn down.

In the performance, the Kaunda suit gets sewn back together, but it is never the same. Syowia believes that history changes and shapes a person. It changes nations even. People and nations can be fixed but can never be the same again after hurtful events.

Personal and universal mythologies

Syowia’s draws inspiration and histories from both Kenya and Germany, where her mother is from. She also studied in Chicago, so a lot of her framework within the art world context comes from that scene. During a brief moment in her 20s, she felt that she had to choose between her Kenyan and her German heritage, but as she grew up, the two became more harmonised. She feels that not everything one does needs to identify geographically, yet accepts that in her work a certain Germanic and Bantu aesthetic is present.

As her work focuses on narratives, memory and DNA, part of her culture is referenced in the work. However, what she finds most interesting is that in different cultures, the same mythologies are shared – the same stories, perhaps under different names. Those are the mythologies and histories that Syowia wants to reference in her work.

Read more: