28 May 2024

Interview

MICHAELA CASKOVÁ: WEATHERING ADVENTURES

Michaela Casková (she/her) is a visual artist, educator, nomadic gardener, host, friend, and forager who keeps an eye on atmospheric events. Walking, observing, listening, mapping, and collecting are some of her tools. Motivated by processes of sharing and learning, Michaela is constantly flowing between collaborative and interdisciplinary processes. Many of her projects involve not only long term observations but also care, hospitality, and the art of companionship. Sometimes she cooks soup, sometimes takes you for a walk with a basket, sometimes you are invited to take part in the artistic process, sometimes the result is a workshop for various audiences… or a little conversation.

Michaela’s Small Talks project is based on fascination, conversations, and everydayness. Through observing and monitoring weather phenomena, she redefines the topic of weather from that of a scientific probability calculation based on accurate data, to an exhibition of visual and sensory metaphors that trace time and tell the stories we are living—our social weather.

As a member of Mustarinda association (Finland), she focuses on projects related to the socio-ecological transformation of society through connecting contemporary art with multidisciplinary research, and hosting residency programs, educational and publishing activities. Since 2019, she has been working under the Department of Biology and Environmental Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä, where she is co-developing teaching materials that convey evolutionary processes and phenomena as part of the Evolution in Action team. In 2023, she collaborated as a member of Mustarinda team, on the Children’s Forest Pavilion representing Lithuania at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Michaela is HIAP alumni from summer 2019 and a long term resident in 2021.

The Weather Cabinet, public artwork commissioned for Oulu Art Museum, 2021, photo by Mika Friman

AA: How do you experience the natural world through walking? Is it a conceptual or a performative experience? Does the art become collaborative, when you walk with others?

MC: Walking has been consciously part of my practice for a very long time and naturally the dynamics and meanings have changed and morphed with each hike, each project, each fulfilled basket, each conversation or silence with my co-wanderers. There have been times, when foraging trips were performative even though I never thought of myself as a performer. I think of myself more of an educator or host, which is quite a performative role even if I try to avoid it. When walking and foraging with others I love how knowledge is transferred, there is so much information that can be shared by pointing to plants, mushrooms and figuring out answers together whilst being in forest. I have learned most of what I know and do from walks with others and from forests themselves which makes my work collaborative from beginning till the end.

AA: Do you find your walks in nature, gathering and foraging, to be relaxing, or do they highlight feelings of ecological anxiety?

MC: I am trying now to move, in my memories, back to the days when I was questioning my practice as a fresh graduate who after many years of coming and going moved to Finland. Obviously I had many things on my mind, but I was also learning how to rethink what is (supposedly) expected from an artist and what do I expect from myself following this path. It is only maybe during the past 5 years that I have had a studio. Already back then I was sensing what I know now – I can not be really dependent on keeping a space in order to create things and to be(come) an artist. Because the responsibility of keeping such space also created tension that I am supposed to produce a lot since I am gifted with such a privilege of having extra space for work. And here we go. There are so many tensions and anxieties in this world and as an artist, and anyone really, one needs to exist in a very delicate balance of being fully involved and yet keep the right amount of distance to tragics of our times, to actually be able to make art and live and survive not only environmental anxieties. And that is what happens to me on my foraging walks, in someone’s garage or in various kitchens, with the nose clicking over steaming pans and the whole of me immersed into the process. My walks and neverending experiments give me such space to take, literally, deep breaths and help me navigate and move forward with my work. For me it is rather hard to create such a state of mind in between the walls of my studio. I think of my studio more as a place of archiving, keeping, hanging out, materials’ resting and doing more or less admin which takes larger and larger amounts of time year by year. It is not a space where the most important part of the process actually happens. That is out there with full pockets and baskets and spruce needles in the hair.

HIAP Open Studios / Material Bank, autumn 2021, photo by Sheung Yiu

AA: Could your artworks be seen as landscapes, metaphorically speaking? They do, after all, represent your surrounding environment.

MC: I love the idea of seeing my works as landscapes! Most of my projects are composed of works derived from last year’s foraging and weathering adventures, woven with routines and chores; it starts with landscaping and evolves into choreography between steaming pans, shaken liquids, and dripping pigments in jars. Repeatedly walking through layers of landscapes, always having something in my pocket. All my foraged and extracted materials leak into the space, fabric, yarn and paper and I am a freak who archives them with notes on weather and character of landscapes they come from. When looking at my works, color charts and stories of inks, I always see the particular spot and landscape in them for sure.

AA: Is your work more about observation or rather thinking and experiencing the landscape or the natural world? Would you describe your work as ecological – or bio art – or is it a process that is about felt experience, such as your reaction to weather, for example?

MC: I always get a very insecure feeling of labeling. I know it is important to be able to articulate and mediate what a person does in their artistic process. But there are so many layers and ways to relate to artistic practice, especially retrospectively speaking. As I mentioned before, my work is often performative, but I never considered myself a performer. You can see in my exhibition paintings, but I do not feel comfortable to be called a painter. I absolutely do not want this answer to become lame or talk a lot without saying a thing. But really, my work very often started with very practical intentions and an urge to learn new skills or craft. Only later on it became an artwork. For example, with the weather and building my material bank it started when I moved to Kainuu to one of the snowiest areas of Finland. Seasons, weather, and climate were very different from what I was used to. I thought I knew quite a bit about growing and foraging, but back then I had to adjust to the gardening season which basically lasts only three months and not a half year. I was tracking down and asking and observing with the urge to make the most out of it. How to manage snow that covers ground for another half year? When do people here actually start planting potatoes? It was inevitable that weather has a huge impact on every single decision around housekeeping and I needed to calibrate, follow others advice and live with knowledge of locals and try to sway with the seasonal flow. That is how my weather tracking started and why it lasts.

Small Talk #13: The Company We Keep, The Cup We Share exhibition at Maatila, Helsinki, 2024, photo by Liina Aalto-Setälä

AA: Do you, in your weather diaries, consider weather in relation to time?

MC: Absolutely. I am keeping weather dairies and have a weather station placed in Mustarinda. I can see from a distance how the house is doing and together with lived experiences from other housekeepers we together build a deep knowledge of the particular place on top of the hill. I have kept a weather diary for years now, with some breaks, in which I obsessively record details about foraging trips and extracted materials in relation to the weather. To me, talking about the weather today means expressing concern and care about our shared futures. The weather also rakes a fruitful ground for metaphors. Is weather-based small talk a conversation starter exactly because it doesn’t reveal the complete story, but allows opening up and bonding over shared universal experiences? What do we really talk about when we talk about the weather? For me, it’s a way to connect my life and work with others, to stay grounded in the world, and to get to know people based on how they frame their experience of what is happening outside our doors.

AA: You participated in the collaborative project Children’s Forest Pavilion, which represented Lithuania in last year’s Venice Biennale. Could you tell us a bit about the process behind the pavilion? Did you educate the children on environmental issues or learn from them?

MC: In autumn 2021, Jurga and Jonas from Neringa Forest Architecture, which operates under the umbrella of Nida Art Colony (Lithuania), arrived with their family for a 2-month residency in Mustarinda. Over the course of two months we discussed the state of forests across the Baltic and Nordic countries and talked about ways to reflect and mediate these themes through art and environmental education and through architecture.

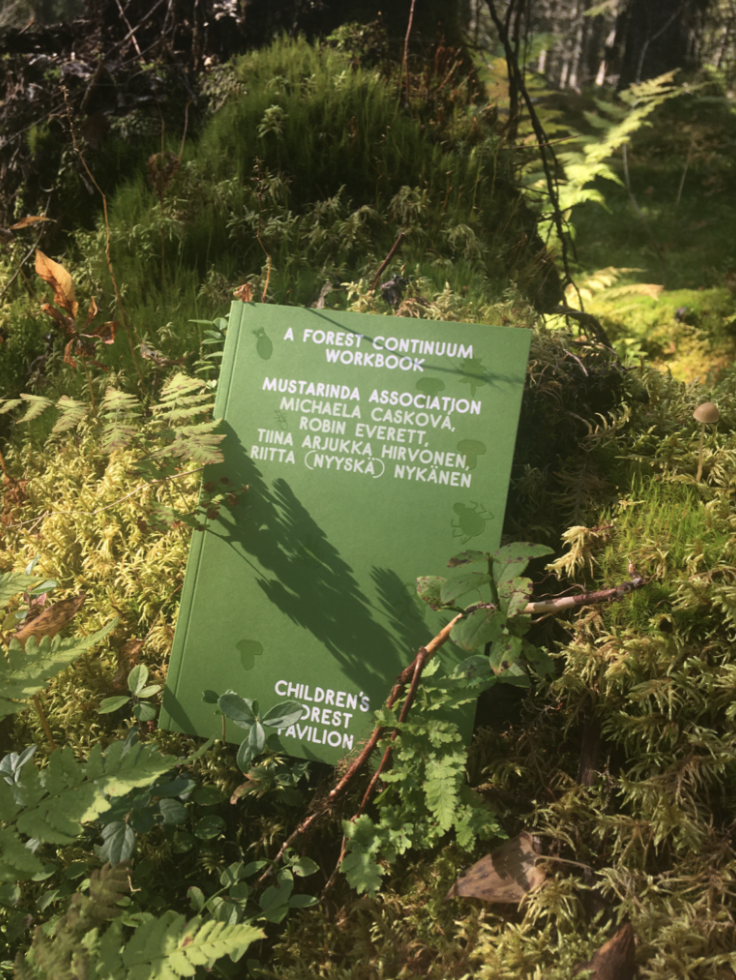

After a year or so, J&J contacted us again to see if Mustarinda would like to join the team of future Children’s Forest Pavilion, which developed into a large collaborative project composed by curators Jurga Daubaraitė, Egija Inzule, Jonas Žukauskas. Although the forest was certainly a subject of NFA’s site-specific research at Neringa municipality on Curionian spit at first, pretty soon the curatorial approach of the pavilion evolved into a pedagogical project, a playscape that became a classroom, playground, library and archive. And that is where Mustarinda got involved. We formed a small team of Riitta “Nyyskä” Nykanen, Robin Everett, Tiina Arjukka Hirvonen and myself and in the autumn 2022, we began to work intensively on the pavilion. We held a series of workshops with local schools in the immediate area around Mustarinda in Kainuu region, which means schools 30-40km away. And later Nyyskä ran workshops for children in Lithuania and Venice. It was important for us to test the same activities in different types of forests. Specifically, in the northern Finland old-growth forest, where spruce is the dominant and naturally occurring tree. And as a counterpart also we encountered the cultivated, intensively managed forest of the Curonian Spit. The artistic processes, the tasks we did with the children during the Mustarinda workshops, then developed into the play space of the pavilion in the form of a documentary film, a room with a screen and a Forest Continuum Workbook full of texts and tasks about the continuity of the forest, its cycles, the non-linear perception of time and time as a keyfactor in increasing the biodiversity of the forest.

The common line for all of us working on the pavilion (which was about 20 members of the team) was to make the children and everyone understand that the forest is a sophisticated system full of cyclical processes and that each individual actor or community has its place in it and that the forest is far from being just trees. The aim of the exhibition was to encourage curiosity in visitors, young and old alike, and to show different perspectives on the forest, not only as a resource to meet human needs. Certainly there was a lot of emphasis that today’s forests are under constant economic and political pressure. We asked ourselves and then the visitors often quite complex and vastly difficult questions about our commons, shared spaces, infrastructure, colonisation of forests and what is the role of architecture in all this… In short, we wanted to explore the possibilities of involving visitors in such difficult topics as the changing current forest space is.

Forest Continuum Workbook, part of Children’s Forest Pavilion at Venice Bienale of Architecture 2023, photo by Michaela Casková

Photos provided by the artist.

More:

https://naposedu.cz/portfolio/

Instagram: earth_of_fox

www.mustarinda.fi

www.evolutioninaction.fi

www.neringaforestarchitecture.lt