15 Aug 2019

Interview

LISA HILLI KNITTING IN FINLAND

Lisa Hilli is an artist currently living in Melbourne, Australia. Lisa has a background in photographic media but is currently interested in exploring textiles in all their variety. She was born in Papua New Guinea, and also has relatives in Finland from her father’s side. With such a diverse background, no wonder questions of belonging and identity are very central to Lisa’s practice. During her summer 2019 residency at HIAP, Lisa has been discovering her Finnish roots while travelling in Western Finland, practicing traditional Finnish knitting, weaving and lace techniques, and exploring questions of identity through photography and textiles.

AA: What or who were your initial influences and what made you decide to pursue textile art?

LH: The earliest textile influence goes back to childhood. An Australian artist and author Jeannie Baker. I remember my teacher in primary school read the story Where the forest meets the sea – a book about the beautiful Daintree Rainforest in northern Queensland. Jeannie creates picture books of life like collages of the world in miniature form in incredible detail which explore environmental themes and connections between humans and landscape. Her work mesmerises me still to this day. Andy Goldsworthy is another artist who has a deep relationship between land, sculptural form and temporality whose work I admired when I first began to study art. Both of these artists use textiles or tactile materials, which are then photographed or documented. Nine years ago, I did cultural exchange with Yolngu master weaver Mavis Ganambarr. I spent four days on Elcho Island in Arnhem Land, Australia learning the indigenous practice of coiling stitch with pandanus leaves from Mavis and other Yolngu fibre artists. I was there with my mother and it completely revived her weaving of bilums, an iconic string bag from Papua New Guinea made by women. I then decided to look at the practices of weaving from the Pacific to see how I could incorporate textiles in my practice. This ultimately led me to finding a historical woven body adornment from Papua New Guinea, called a midi, which museums refer to as a ‘shell collar’. It’s a regal item worn by men around the neck covering the chest area with up to 30 rows of nassa shells threaded on natural fibre. It was an item of status that became culturally devalued and transformed through colonial impact. The midi became the focus of my Masters of Fine Art research degree. I re-made a midi in 2015 – the first to be made in over 100 years.

Midi, Lisa Hilli 2015. Photographer Keelan O’Hehir.

Textiles are as old as humans. Every society across the world has a form of textile practice that is a language in itself, that communicate ritual, customs and signifiers within those communities and those who are able to read it. I wanted to understand the language of textiles. When I began to gain an interest in this material language an artist called Eddy Carroll appeared in my life, literally! I got a random email from her inviting me to travel to Turkey for a bi-annual craft event that takes place in the municipality of Silje, a town known for its linen. Eddy lives and works in Melbourne. She creates soft sculptural forms. Together, Eddy and I undertook the first collaborative artist residency at the Australian Tapestry Workshop and worked on our own projects whilst watching and observing each other’s process in a very productive and stimulating tapestry environment. Eddy taught me and helped me understand the ways language could be communicated through textiles. We created a work together called Wuwung Vargil (I give you something and you give me something back) which combined photography and both of our textile practices. I turned to textiles after years of working with photographic media. I found that editing digital videos and still photography to be an isolating process. It’s just you and the computer. I’m able to work on a textile piece whilst still having a conversation with someone else. You can’t do that with a computer in front of you.

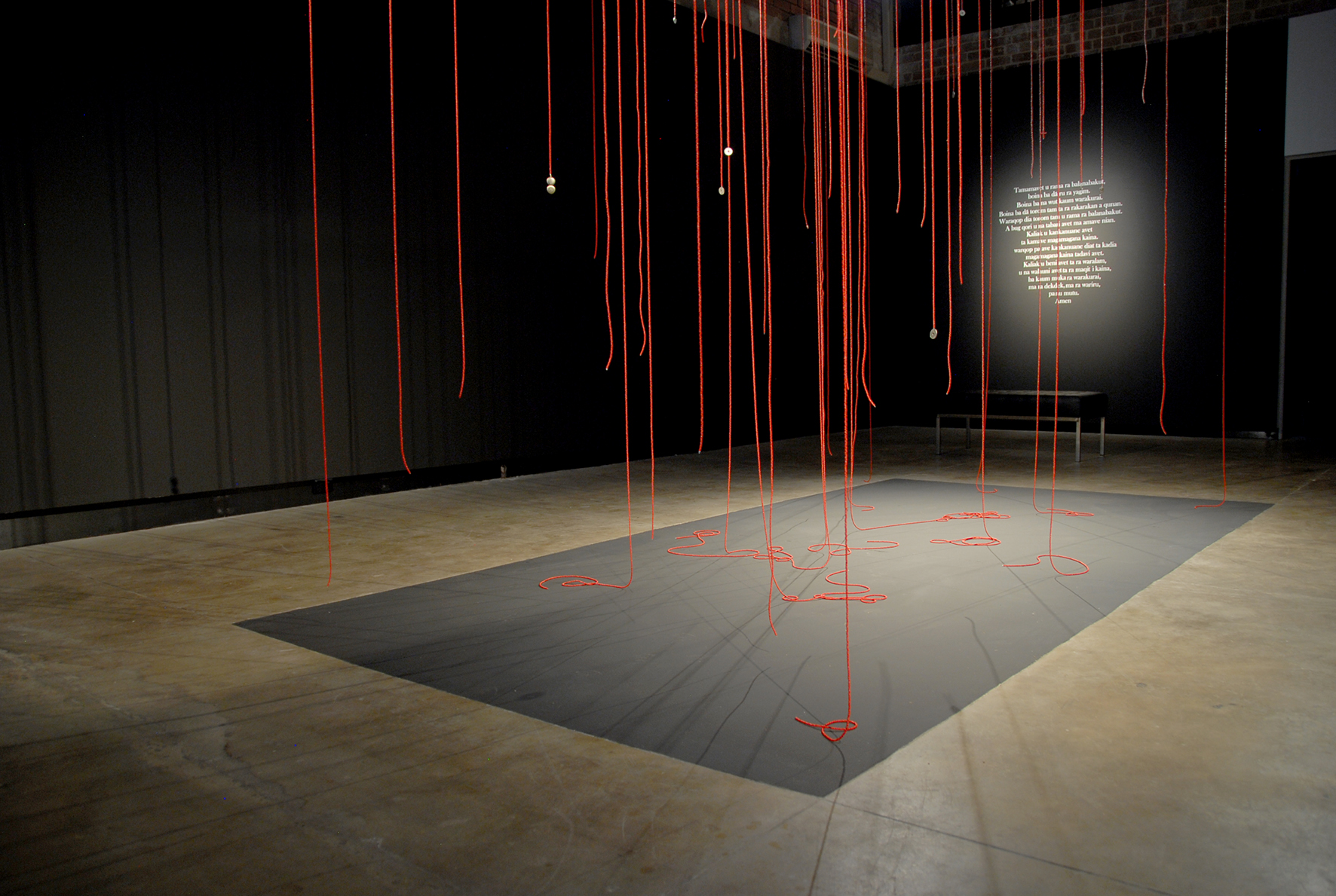

Sisterhood Lifeline, Lisa Hilli 2018. Photographer Markus Ravik.

The time it takes to make something with your hands physically is bound up with so much meaning and value of many things that humans hold dear. Things like memory, protection, identity, status, currency and story can all be found in different types of textiles. It is the human labour involved in making textiles that I value and appreciate. The time it takes, the scarcity or abundance of material implies differing values. There’s a human touch in textile or tactile materials that digital technologies cannot replicate.

AA: One of the key themes you address is cultural identity and belonging. How do you align the personal with the political in your work?

LH: My personal experiences of the world and the way that the world perceives me is often channeled through what I make. My whole being as a cisgendered woman of colour is political without choice in Western society and art history. I use my art practice as a vehicle to examine my personal experiences, which at times is quite cathartic. The making process for me is labour and time intensive and it’s through this process that I figure things out conceptually and intellectually, which then feeds into a broader political sphere. An example of this is my most recent commissioned work Sisterhood Lifeline. This new body of work was a creative response to institutional racism that I experienced in my workplace. There is so much emotional and psychological labour that I do in my day to day experiences of living and as a museum professional. It’s exhausting. I live in a society that isn’t designed for me or people who look like me to succeed based on my cultural identity alone. Because of my physicality, I am unable to escape the racial politics of my personal experience. I don’t ‘blend in’ with the majority of the population. Racism and people’s anxiety or fear about their perceptions of me is not my issue. There’s not much I can do about that personally. What I can do as an artist is to visually reflect back to society the world that I live and breathe in.

AA: How is your work inspired by or influenced by nature and your surroundings?

LH: In Papua New Guinean cultures land is intrinsically tied with lineage and identity. I am from a matrilineal society, the Gunantuna (Tolai) people and the ownership of land is handed down through women. We also trace our lineage through women. Every single vunatarai (matrilineal clan group) is identified by a totem or reference to land. I created a body adornment piece Vunatarai (matrilineal) armour that references this matrilineal system through collaged photographs of vividly coloured tropical plants. Throughout my residency I have been documenting the conscious and unconscious influences that have inspired my thinking and making. This has largely been textiles and the use of them for practicalities in the day to day. My eyes have been very much attracted to ropes, particularly on ships and the water ferries around Helsinki and rag rugs! The sound of ships and constancy of seeing people in boats and ships gave me insight into the culture of Finnish people. It also made me think of the kind of work my grandfather would have done as a merchant marine when he still lived in Finland. I’m certain he would’ve known a few rope knots. The sight of so many beautiful wildflowers on the island has made me think about the significance of flowers and nationhood. This has seeped into a commission I’m currently working on for the Australian War Memorial, where I’ve incorporated flowers into a digital photographic collage representing nationalities of interns held in a prisoner of war camp in Papua New Guinea during World War 2. All of our environments have conscious and unconscious influences and conditionings over time that make up the complexity of our individuality, communities and social behaviour. That alone fascinates me.

Vunatarai (matrilineal) Armour, Lisa Hilli 2015. Photographer Keelan O’Hehir.

AA: It is a fact that textile work as art and craft has been traditionally viewed as feminine both in general and in the art world. This is something that you explore in your art. Could you say something about this?

LH: My practice has its foundation in photographic media. Textiles is something that seamlessly evolved in my practice and I’ve fallen head over heels in love with it! In the Pacific region, it is common for women to spend time together, collectively weaving mats or bags for utilitarian needs. This still happens today. In 2010, I helped establish a weaving group for Pacific women living in Melbourne, as a way to connect and share cultural knowledge. These gendered spaces are very important for individuals to bond, build relationships, pass on cultural knowledge and to feel safe. I love what British artist and academic Lubaina Himid describes in regard to textiles – “painstaking effort, optical possibilities, audience participation, the secret language of women.

With the exception of tapestry, textiles are not always given equal standing as ‘fine art’. So many female artists and feminists have used textiles to protest gender inequality, especially in the art world. It was men who decided what was considered ‘fine art’ historically and anything that was made with a needle or was women’s work was not considered art. Something that I can’t help but notice is that there are quite a few well known men, globally, who use textiles in large scale works or installations, who have very high profiles in the art world. How many high-profile female textile artists can you name? Women historically have been restricted by what they access to in patriarchal societies, some of these restrictions were access to education, child rearing, body autonomy and employment. When you’re socially and economically repressed you use what you have access to. Writing with a needle so to speak. Customary craft practices like knitting, sewing, weaving had a functional form as an essential human need. To use your craft in a way that goes against the practical is a political act. It makes sense for me to use textiles with the complexity of my cultural and political perspectives. I use textiles to insert myself and my practice into a feminine history and to contribute and continue a practice that is as old as humankind.

Value Systems, Lisa Hilli, 2018. Photographer Lisa Hilli.

AA: In your work, you seek to build relationships and create connections between communities. What have you been working on and how have you been invested in the Finnish culture whilst at HIAP?

LH: I’ve invested most of my time in learning specific weaving and braiding techniques from the Nordic region. I’ve been teaching myself Språng and Nålbinding, the oldest form of knitting. I also re-learned a figure 8 stitch from my mother which is used in Papua New Guinean bilums. I interestingly found some similarities between the Nordic and Papua New Guinean techniques. I also visited Rauma to attend the Lace Festival. I even had a chance to learn how to make lace! I wanted to learn these age-old weaving / knitting techniques to acquire new knowledge and apply this through different use. Industrialisation has devalued many craft and textile practices and skills, which were once incredibly valuable and essential for human survival. Weaving forces you to use all of your fingers and keeps distracting mobile devices at bay.

The first two months of the residency I homeschooled my 10-year-old son. Together we learned a lot about Finnish culture; we both love history, so we started researching what Finnish people value culturally. We’ve been listening to Jean Sibelius, reading Tove Jansson. My son now has a coffee addiction. I attempted to read the Kalevala and was equally thrilled to discover that it was this collection of poetry and runes that sparked a movement for nationhood. I love the word sisu. My son loves military history, so he updated his knowledge of the Winter War. I understood the meaning of sisu when he explained the tactics used by the world’s greatest sniper, a Finnish man known notoriously by the Russians as “The White Death” – awesome. I found the pre-historic exhibition at the National Museum fascinating. This gave me great insight into the historic textiles that I was learning as well as many other things. I had my first sauna with a Finnish family who live in Jeppo / Jepua, western Finland, where my grandfather is from. This was a very special family pilgrimage for me as I got to meet relatives and walk in the footsteps of my ancestors.

I’ve mostly made connections with local people who live on Suomenlinna (Suokki) and the other HIAP artists of course. There were two key artists that I was hoping to connect with during my time here in Helsinki, but they are both overseas. However, I’ve just made a connection with a Saami woman and am hoping to travel up to Lapland next week! My greatest investment in Finnish culture has been eating as many berries as possible.

Read more:

Artist website

The Commute, Institute of Modern Art

Dress Code, Museum of Brisbane exhibition review