21 Dec 2020

Interview

EFFROSYNI KONTOGEORGOU: SOFT CORALS AND STRONG FORTRESSES

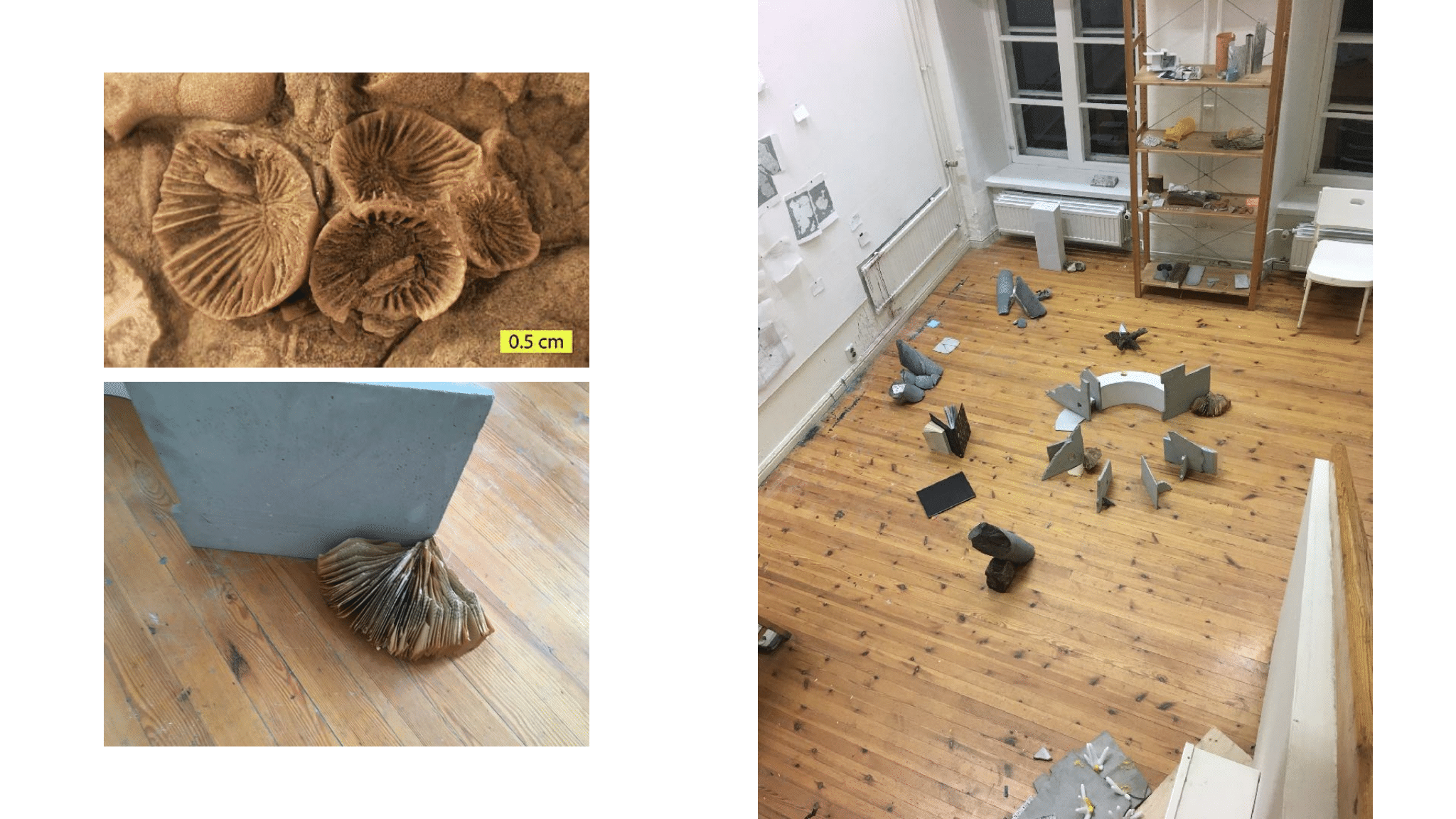

Between September and November, Effrosyni Kontogeorgou spent her time on the island of Suomenlinna walking around the fortress, observing details and collecting materials. She noticed interesting patterns on the walls of the fortress and marble floors of the buildings, which she was delighted to discover were fossils of marine organisms from thousands of years ago. Fossils fascinate Effrosyni, as do corals. Corals, while being animals, resemble both stone and plants, and they are simultaneously soft and hard, fragile but adjustable. The soft interior of the coral develops a hard, calcified outside layer, and once Effrosyni describes her thinking, the metaphor seems crystal clear: the coral is the fortress, the hard exoskeleton having been built to protect what is inside.

During her time at HIAP, Effrosyni enjoyed the time spent with her fellow residents sharing ideas, potentially even leading to future collaborations or friendships. The voluntary isolation of the island was intense, Effrosyni feels, ideal for developing ideas for new works, researching, learning, and asking questions rather than answering them.

Work in progress, studio view. EK: “In addition to other found objects from the island of Suomenlinna and material remains from former HIAP residents, I am particularly grateful to Baran Çağinli, whose work remains in the Elias studio offered me a unit for my study, and to Jessie Bullivant, who notified me to collect the historical building cores.”

AA: Does it often happen that a specific geographic locale influences or gets absorbed into your visioning of an art installation? If so, in what ways?

EK: For the last 5 years site-specificity has been an orientation method for me. The invitations I received to exhibit work of course influenced where I worked, usually indoors. A gallery, church or a museum with its contextual information influences my work. Most of the spaces, especially institutional ones, are charged with previous experiences, certain “grammatical” information that “tell us” or sometimes “dictate” how to behave and move. My approach on site begins mostly intuitively, afterwards I plan. My body experience within the space and the others involved inform my work in various interdependent ways. It depends really on discussions, (hi)stories, observations, associations, or an instance that draws my attention. And then I begin to formulate questions, images and collecting information around it. For example, irregularities on an architectural plan, a flow of visitors or the air in a museum, a closed door that is not clear where it leads, a viewpoint or a landscape, or simply how my work possibilities and limitations are negotiated in terms of the institutional regulations.

When I conceive an intervention, I am always thinking also of the visitors: their movement, behavior, expectations within the specific space and perhaps all the rest that is going on and we cannot control. Even if I have certain ideas or reasons for deciding that instead of something else, at the end there should be enough open space for interpretations, to be (full)filled by the others! When I cannot fully control what happens, it becomes surprising for me too.

AA: While your work is often playful and clever, your use of industrial materials, colors, and their site-specific installation appear minimalistic and almost serious. How do you approach looking at a space and determining what to make for it?

EK: I don’t think I am only minimal or serious, sometimes there is a lot of childish playfulness there too. Yet I understand what you mean. Most of the work is not easy to “experience” by a two-dimensional photo documentation, as it was always the case with site-specific works. The answer to minimalism is easy though. I adapt to my surroundings or I appropriate certain elements, materials or colors from my direct surroundings. In that way, often the artwork integrates in the architecture and disappears as an object or even as autonomous artwork. That can have various impacts also on perception. The space itself informs the body. The visitor for example can step on the “artwork” without knowing that it is an artwork or without instructions to participate. Still this homogenous appearance is only phenomenological. There are also disruptions, discontinuities, breaks and irritations between the visitor and the space, which question this in-between state of being.

Force majeure or how the flap of a reed warbler’s wings set off a downpour 2020, site-specific installation, aluminum checker plate, zinc profiles, PVC pipes, water, filter, rain barrel, pump, electronics. Photo: Franziska von den Driesch.

AA: Natural elements – especially air and water – seem to have a strong place in your practice. Do you wish your audience to consider the impermanence of both the art installation and, say, rain?

EK: Sometimes I find it more challenging to create a state of impermanence or a transitional state with building materials or constructions that appear as if they have always been there. My installations though were never permanent. The space undergoes temporarily a change, then it is gone. Some of the material can be later reused. Time-based processes, movement and elements such as light, water and air have been also important aspects in my practice. For example, in my last installation “Force majeure or how the flap of a reed warbler’s wings set off a downpour”, the simulation of rain can be playful, poetic or raise questions simultaneously. Depends on the moment, what connections you want to see and how you react on site. Even not perceiving it as an artwork, belongs to this.

The back door of the gallery, which was previously closed and only marked as an emergency exit has been opened, creating a visible threshold from both sides indoors and outdoors. The sudden rain appears on the first impression perhaps poetic and the sound in the gallery surprises both the visitors and the passersby on the street. Especially because the event happens in intervals and is not isolated in the gallery, there is so much happening around it uncontrollably. It is like opening up a sterile “laboratory of life” (in this case I mean the gallery) and comparing it with the life itself outdoors, with all its beautiful mess. The actual weather compared to the simulation, the people passing or bathing at the river outside, the splashing water turning into a puddle indoors, the “unwanted” plants that grow on the stairs blocking an easy entry and finally a bird flying from its nest directly underneath the staircase and literally setting off the rain in unpredictable intervals.

This work for me opens parallel perspectives between human and nature, institution and what we call simultaneity, predictability and control.

It seems to me almost absurd, when a water puddle for example, a phenomenon we confront everyday outdoors, on the street or in a park, becomes a threat as soon as it intrudes a gallery. Still from the perspective of a public institution there are really complex legal and safety matters connected to it. The maintenance of the installation was very challenging, and I am really grateful for the support of the house-team and the curator who made it possible.

Force majeure or how the flap of a reed warbler’s wings set off a downpour 2020, site-specific installation, aluminum checker plate, zinc profiles, PVC pipes, water, filter, rain barrel, pump, electronics. Photo: Franziska von den Driesch.

AA: It seems that you often connect, in your work, elements of architecture with aspects of nature. How does nature inform your practice as an artist?

EK: My interest in architecture started already in 2010 with my master thesis “The malleable house,” which was a collaboration with Athanasios Kanakis. Back then the approach was mostly poetic or metaphysical inspired by diverse theories, among others “The poetics of space”, a book by Bachelard on utopian, day-dreaming spaces. A house is first of all built to protect us from the forces of nature. There it starts perhaps with a separation, but the house has windows and frames that select and let forces and living beings also come in. For example, at Suomenlinna, in the residency houses we all had regular visits by the local birds, flying daily indoors through an open window. They were great company! A surprising visit in my studio by one of them offered me also a gift, the video “A studio guide-tour by a great tit.”

My artistic method and approach towards nature is not yet crystallized. Perhaps it is not even necessary to be crystallized. My questions towards nature and our co-existing living environments began from an impulse to change. For my work not to be merely self-referential and to find a position in relation to what happens around me, not only site-specifically, but also in a bigger “worldly”-reference. My stay at HIAP offered me a time to read about related topics, to exchange ideas with fellow colleagues, to research my intentions and how other artists deal with similar ideas, as well as to experiment and get lost in different directions. I had the privilege to even try out things which didn’t work or are not yet ready (we usually talk too little about those unfinished processes).

Work in progress, studio view. EK: “In addition to other found objects from the island of Suomenlinna and material remains from former HIAP residents, I am particularly grateful to Baran Çağinli, whose work remains in the Elias studio offered me a unit for my study, and to Jessie Bullivant, who notified me to collect the historical building cores.”

AA: During your time at HIAP, you have researched similarities between the architectural structures of the Suomenlinna fortress and those of coral reefs, which as we know, are imperiled by global warming all over the world. Have you previously made work about climate change and the loss of biodiversity?

EK: The global warming and the loss of biodiversity are critical ecological questions that brought the importance of coral reefs and especially the acidification of the oceans in the foreground of media attention, science research and environmental discourse. However, in my role as an artist, I see only a possibility to intervene in the narratives and metaphors related to nature. During my stay at Suomenlinna, the book Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino was a compass for my approach to superimpose structures between Suomenlinna fortifications and the coral reefs. Each fictive story by Calvino is based on one scientific discovery of his time. Though some of those scientific “facts” are considered today already to be false. (Pre)historically, scientifically and culturally corals have become so many things, and they have also inspired myths of transformations, between plant, animal and stone. While they grow, some of them, especially those that are threatened by ocean acidification, secrete a stony calcified fort; an exoskeleton or armor for protection. Similarly, we have a history of building defence walls and tunnels for protection. Though it comes a moment in time, when a method becomes obsolete or a relic of a previous times, as is the case with the Suomenlinna fortress. Even if we confront today many uncertainties, it motivates me to think that nature has still many transformative stories to tell.

Photos provided by the artist.

Effrosyni Kontogeorgou’s residency was organised as a collaboration between HIAP and Künstlerhaus Bremen.

Read more:

http://effrosyni.net